27

AUGUSTO CÉSAR BARJONA DE FREITAS

PORTUGAL

© Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro

1834 – 1900

ANCIEN MINISTRE DE LA JUSTICE INITIATEUR DE L’ABOLITION DE LA PEINE DE MORT AU PORTUGAL EN 1867

RESSOURCES :

-

De L’Abolition

-

Gilberto Jerónimo: World and European Day against the Death Penalty 2021

-

Os Crimes de Diogo Alves, 1909 by João Freire Correia & Lino Ferreira

-

Quiz

-

Jeu Si vous étiez un juge

La peine de mort est la « peine qui paie le sang par le sang, qui tue mais ne corrige pas, qui venge mais n’améliore pas. »

Augusto César Barjona de Freitas

Précédent

Suivant

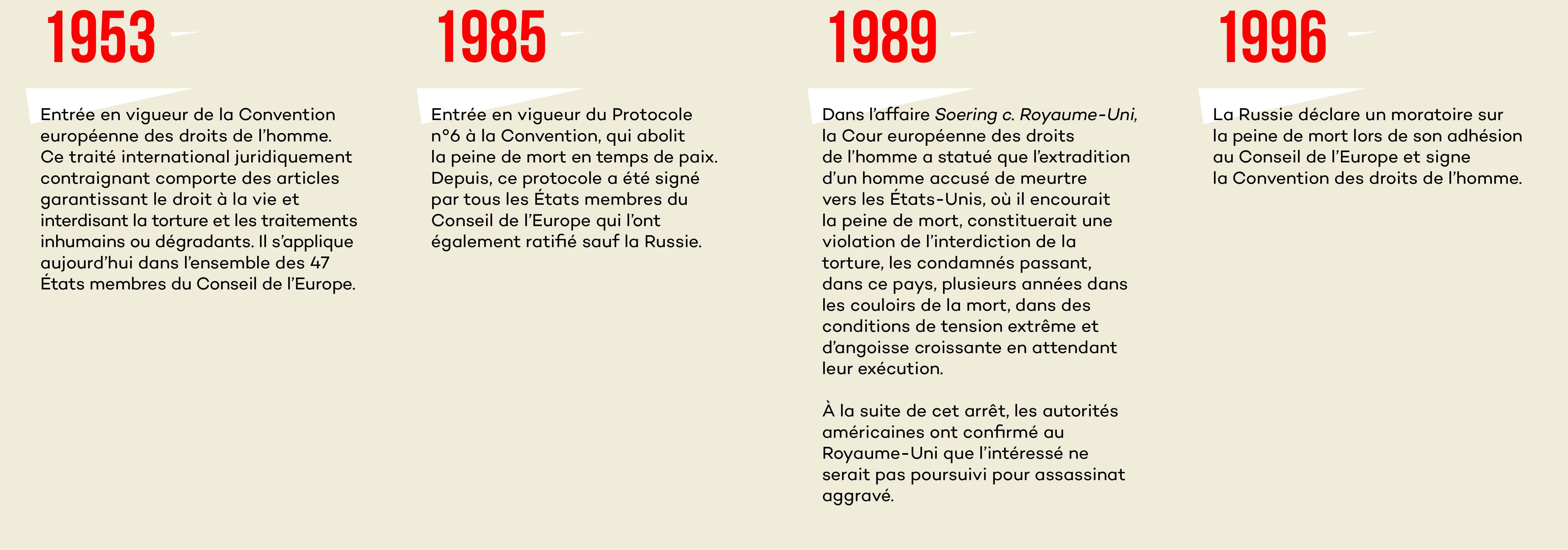

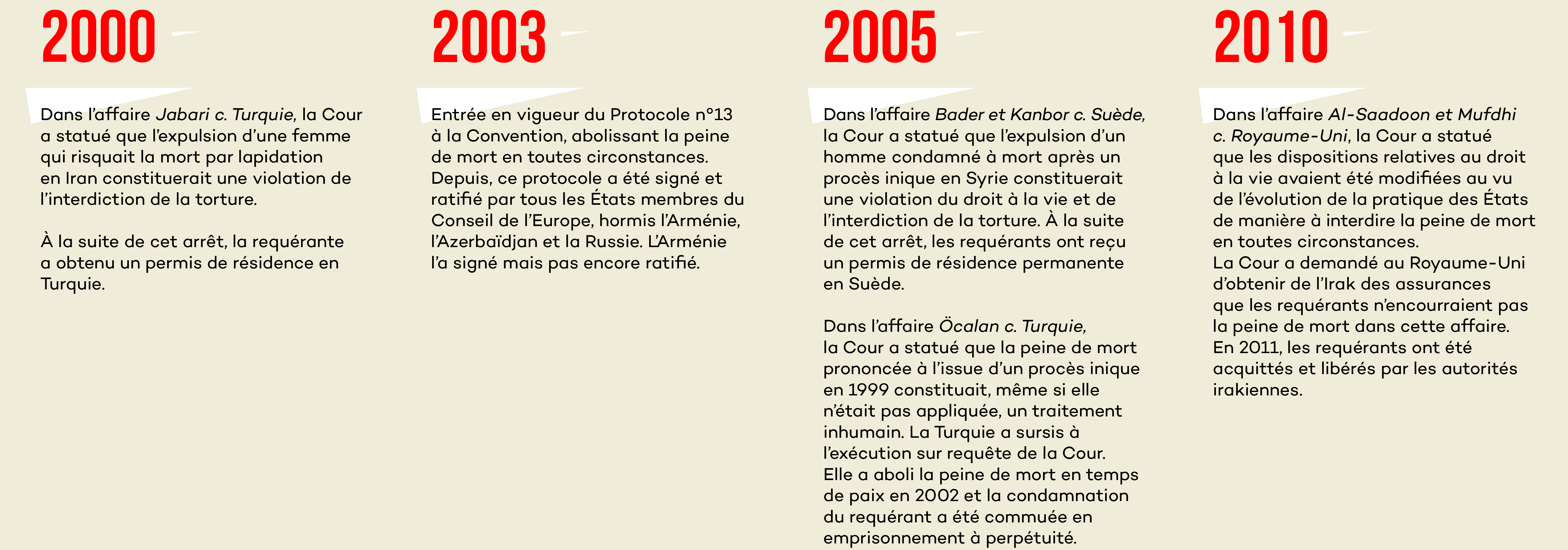

Juriste, professeur de droit, député et ministre – notamment des Affaires ecclésiastiques et de la Justice -, Augusto César Barjona de Freitas a mené d’importantes réformes telles la réorganisation judiciaire et administrative, mais surtout l’abolition de la peine de mort. Le Portugal est le second État à abolir après la Toscane1, et donc le premier Pays de l’Union européenne, même si cette entité n’existait pas encore. Et si l’influence de l’UE n’a en aucun cas orienté sa décision, le Portugal porte en lui les fondements de la valeur abolitionniste, promus aujourd’hui par l’ensemble des États européens.

Alors qu’aucune femme n’a été exécutée au Portugal après 1777, et aucun homme depuis 1846 {je tombe sur 1846 ET 1849, avec plusieurs occurrences pour les deux dates : c’est un problème}, dès 1852, Manuel José Mendes Leiten présente à la Chambre des députés une proposition d’abolition de la peine de mort pour délits politiques. Cela donne lieu à « l’Acte Additionnel à la Constitution ». En 1863, les Chambres décrètent l’abolition de droit, mais leur décision ne reçoit pas l’assentiment royal. À partir de cette propédeutique, le ministre Augusto César Barjona de Freitas propose l’abolition de la peine de mort pour tous les crimes, à l’exception de la trahison pendant la guerre. Il décrit la sanction capitale comme la « peine qui paie le sang par le sang, qui tue mais ne corrige pas, qui venge mais n’améliore pas et qui, usurpant à Dieu les prérogatives de la vie et fermant la porte au repentir, éteint dans le cœur du condamné tout espoir de rédemption, opposant la faillibilité de la justice humaine à l’obscurité d’un châtiment irréparable ».

Le projet de Barjona de Freitas, est présenté à la Chambre des députés les 9 et 10 février 1866. Il est approuvé, ainsi qu’à la Chambre des pairs, et fait remarquable, avec uniquement deux abstentions et deux voix contre. La loi, pionnière et consacrée par le roi Luís, est publiée le 1er juillet 1867. Elle stipule à son article 1, l’abolition pour les crimes civils. De façon notable, le décret du 9 juin 1870, est étendu et appliqué aux colonies. La question du rétablissement de la peine capitale n’a jamais été posée depuis lors. Cette abolition précoce, l’a été durablement. Néanmoins, il faut la Constitution de 1976 – soit après la chute de Salazar -, pour que soit aussi abrogé le châtiment suprême pour les crimes militaires.

Source d’inspiration européenne, se référant à d’éminentes figures de la pensée des Lumières – notamment Beccaria –, cette action politique est aussi très influencée par la Franc-maçonnerie, très présente au XIXe siècle au Portugal, comptant nombre de députés, ministres, pairs du royaume et hauts fonctionnaires, portant un idéal humaniste. En parallèle à la loi d’abolition est proposée une réforme pénitentiaire, développant un régime carcéral innovant, en opposition à la justice punitive : régénération et réinsertion des individus dans la société via l’enseignement, exercice d’une profession rémunérée, alphabétisation, etc.

Pour le Français Charles Lucas (1803-1889), les États les Etats de moindre influence politique sont indispensables à l’équilibre des nations européennes car ce sont eux qui appliquent des réformes qui semblent plus ardues à mettre en œuvre dans de grands pays démographiquement imposants. Ces derniers prennent ainsi exemple sur la réussite de leurs « petits » voisins pour à leur tour modifier leurs législations, une fois la pratique consommée et démontrée comme efficiente. Lucas théorise que la peine de mort et la question de son abolition sont liées directement à la puissance économique, à la grandeur d’une nation sur la scène internationale ainsi qu’à la démographie d’un pays. Comme si les grandes nations sacrifiaient leur grandeur morale à leur grandeur politique. Ce visionnaire considère que la loi portugaise de 1867 confirme un mouvement qui va se généraliser à l’ensemble de l’Europe, jusqu’à aboutir à une abolition totale sur le continent, grandes nations comprises.

En 2015, la Charte de la loi d’abolition de la peine de mort a reçu la distinction du Label du patrimoine européen. Aujourd’hui, ce document est un point de référence dans la promotion des valeurs, des normes et des principes, de la citoyenneté européenne. Il s’agit d’un jalon de la mémoire historique européenne qui consacre le droit à la vie.

Victor Hugo, le 15 juillet 1867, exprime ses félicitations au Portugal pour l’approbation de la loi : « Le Portugal vient d’abolir la peine de mort. Suivre ce progrès, c’est faire un grand pas pour la civilisation. À partir d’aujourd’hui, le Portugal est le chef de l’Europe. Vous, le peuple portugais, n’avez jamais cessé d’être d’intrépides explorateurs. Autrefois, vous avanciez à travers l’Océan ; aujourd’hui, vous avancez dans la Vérité. Proclamer des principes est encore plus beau que découvrir des mondes ».

Marie Bardiaux-Vaïente

[1] La Toscane – alors indépendante avant son rattachement à l’Italie -, est le premier État abolitionniste au monde. Léopold, Grand-duc de Toscane, abolit la peine de mort en 1786, suite à l’exposé et à l’influence de son conseiller, Cesare Beccaria. Ce dernier a fait paraître en 1764 le premier ouvrage traitant de l’abolition de la peine de mort Des délits et des peines.

- livre

De L’Abolition

Auteur : Charles Lucas

Date de publication : 1869

Editeur : Kissinger’s Legacy

De L’Abolition De La Peine De Mort En Portugal (1869)

- podcast

- vidéo

- quiz

Augusto César Barjona de Freitas

- activité

Partagez sur

Professional writers are the best option if you need to get your essay written. They will ensure that the work meets your expectations and deadlines.This will help to keep your do my essay for me concise and make it easier for your readers to follow the argument you are attempting to make.The best services will give you guarantees that cover everything from delivery and quality as well as plagiarism and originality. Additionally, they will provide the option of a refund as well as free revisions.