13

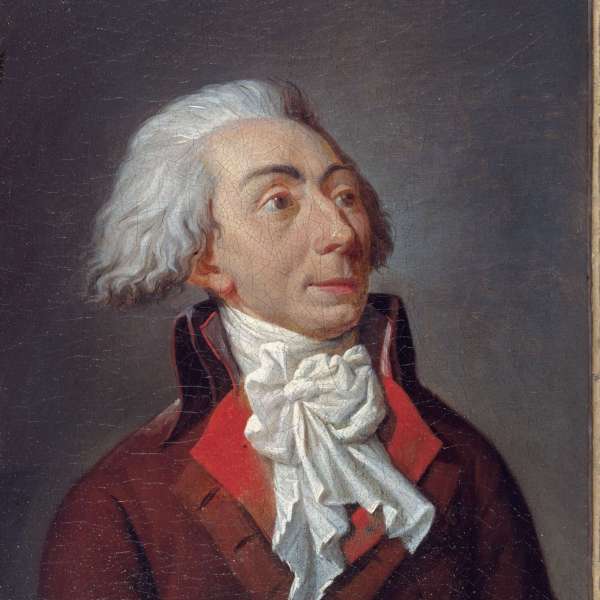

LOUIS-MICHEL LEPELETIER DE SAINT-FARGEAU

FRANCE

Huile sur toile attribuée à Jean-François Garneray

Paris, musée Carnavalet

© Paris Musées

1760 – 1793

Homme politique, rapporteur du premier projet de loi demandant l’abolition de la peine de mort en France (1791)

RESSOURCES :

-

Louis-Michel Lepeletier de Saint Fargeau

-

Danton

-

Le meurtre du député Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau

-

Quiz : Saint Fargeau

-

Le petit bourreau de Montfleury

« Considérez cette foule immense que l’espoir d’une exécution appelle dans la place publique. […] Messieurs, ce n’est pas à un exemple, c’est à un spectacle que tout ce peuple accourt. »

Louis-Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau

Précédent

Suivant

La France est le premier pays au monde à débattre en son Parlement[1] de la question de l’abolition de la peine de mort lors de la rédaction du Code pénal de 1791. Le rapporteur du projet, Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau, se prononce pour l’abolition complète de la sanction capitale, avec pour premier argument l’idée d’une prison qui va permettre de réinsérer le condamné, de l’améliorer. Louis-Michel Le Peletier, marquis de Saint-Fargeau, est élu député aux États généraux, et membre du Comité de jurisprudence criminelle. Il présente en son nom le projet de code pénal. Ce qu’il souhaite et réclame, c’est adoucir les peines, rendre condamné meilleur et enfin abolir la peine de mort. Lors des débats des 23, 30, 31 mai et 1er juin 1791, les députés utilisent d’ores et déjà toute la gamme argumentative qui ont agité ensuite les assemblées pendant près de deux siècles. L’ensemble des raisonnements est dès à présent produit.

Louis-Michel Le Peletier est très vivement soutenu par Duport, Pastoret, Condorcet et Robespierre qui prononce dans l’hémicycle ce qui reste aujourd’hui encore comme un des plus grands discours abolitionnistes : « Je viens prier […] les législateurs qui doivent être les organes et les interprètes des lois éternelles, que la divinité a dictées aux hommes d’effacer du code des Français les lois de sang qui commandent des meurtres juridiques, et que repoussent leurs mœurs et leur constitution, nouvelle. Je veux leur prouver : 1° que la peine de mort est essentiellement injuste ; 2° qu’elle n’est pas la plus réprimante des peines, et qu’elle multiplie les crimes beaucoup plus qu’elle ne les prévient[2]. » Pour les abolitionnistes, les arguments majeurs sont ceux de la barbarie de la sanction capitale, l’effet non dissuasif de cette peine et le risque d’erreur judiciaire.

Pour Le Peletier, « l’une rend irréparables les erreurs de la justice ; l’autre réserve à l’innocence tous ses droits dès l’instant où l’innocence est reconnue[3] ». La foi chrétienne est mise en avant dans le cadre de la contradiction avec le principe de Rédemption : « L’une, en ôtant la vie au criminel, éteint jusqu’à l’effet du remords ; l’autre, à l’imitation de l’éternelle justice, ne désespère jamais de son repentir ; elle lui laisse le temps, la possibilité et l’intérêt de devenir meilleur[4]. » Le mauvais exemple donné par l’État a un poids conséquent lui aussi dans son argumentaire : « L’une endurcit les mœurs publiques ; elle familiarise la multitude avec la vue du sang ; l’autre inspire par l’exemple touchant de la loi le plus grand respect pour la vie des hommes.[5]» En outre, il ne cesse d’appuyer l’idée philosophique selon laquelle il ne faut en aucun cas confondre justice et vengeance. Pour réfuter ses contradicteurs, il justifie sa démonstration par l’exemplarité d’une peine à la fois longue : « L’une est peu répressive sous les divers rapports de la brièveté de sa durée[6] », et publique : « Les portes du cachot seront ouvertes, mais ce sera pour offrir au peuple une imposante leçon. Le peuple pourra voir le condamné chargé de fers au fond de son douloureux réduit, et il lira tracés en gros caractères, au-dessus de la porte du cachot, le nom du coupable, le crime et le jugement. Voilà quelle est la punition que nous vous proposons de substituer à la peine de mort[7]. » Malgré ces élans, la majorité vote le maintien de la peine capitale en instaurant la décapitation par la guillotine comme mode d’exécution. La Révolution a besoin de moyens pour éradiquer l’Ancien régime. Elle considère l’échafaud comme lui étant nécessaire.

Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau est assassiné le 20 janvier 1793 par un royaliste, pour avoir (paradoxalement, si l’on s’en tient à ses positions sur la question abolitionniste de 1791) voté la mort de Louis XVI.

La Convention répond à cet acte de fanatisme en décernant à la victime les honneurs du Panthéon.

Marie Bardiaux-Vaïente

[1] L’Assemblée nationale constituante qui perdure du 9 juillet 1789 au 30 septembre 1791.

[2] Robespierre, Le Moniteur universel.

[3] Le Peletier, marquis de Saint-Fargeau, « Le Moniteur universel ».

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

- livre

Louis Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, Premier martyr de la révolution

Auteur : Florence Frigola-Wattinne Pays : Italie

Genre : biographie

Date de parution : janvier 2015

Cette biographie historique retrace la vie du jeune révolutionnaire Louis-Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, ci-devant noble de robe, puis successivement député monarchiste constitutionnel à l’Assemblée constituante, Président du Directoire de l’Yonne, député montagnard et jacobin à la Convention nationale, enfin régicide inconditionnel lors du procès de Louis XVI. Ses orientations et revirements politiques rendront bien critiques ses anciens pairs mais surtout entacheront durablement sa renommée, bien qu’il eût apporté une juste contribution à la réforme du droit pénal et conçu un projet innovant en matière d’instruction publique… Pour avoir voté la mort du roi sans appel ni sursis à exécution il sera blessé à mort par le royaliste Pâris quelques heures avant la décapitation de Louis XVI. Sacré martyr de la Liberté il sera aussitôt panthéonisé, et un culte national lui sera rendu.

- film

Danton

Réalisé par Andrzej Wajda

Sortie : 12 janvier 1982

Durée : 2h 15min

Genre : Historique, Drame

Paris, au printemps 1794. Depuis septembre 1793 règne la Terreur, où la faction perdante, ici les moins extrémistes, sont menés à la guillotine. Le député montagnard Danton a quitté sa retraite et gagné Paris pour appeler à la paix et à l’arrêt de la Terreur. Populaire, appuyé par la Convention et des amis politiques qui ont de l’influence sur l’opinion, notamment le journaliste Camille Desmoulins, il défie Robespierre et le puissant Comité de salut public.

- podcast

Le meurtre du député Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau

- quiz

Louis-Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau

- pour aller plus loin

Le petit bourreau de montfleury