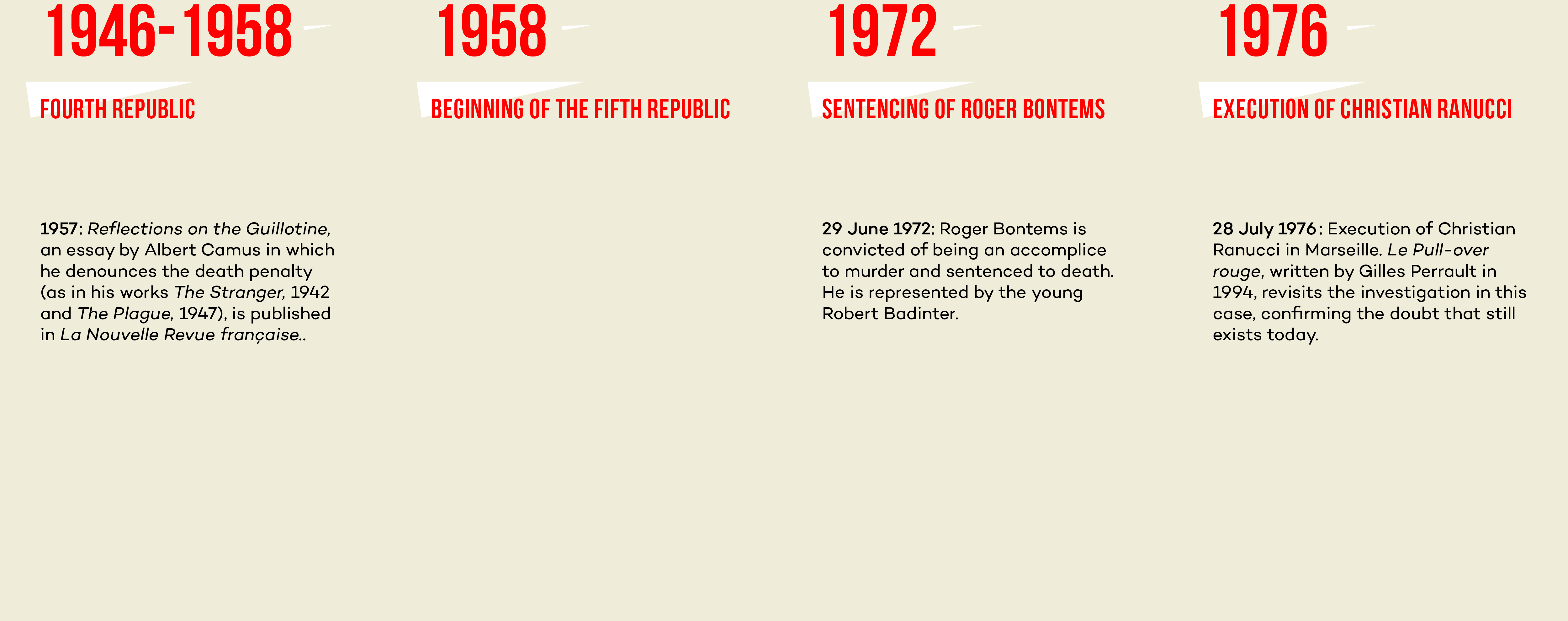

19

CHRISTIAN RANUCCI

FRANCE

Excerpt from the oral argument delivered by Paul Lombard, lawyer for Christian Ranucci, before the Assize Court of Bouches-du-Rhône on March 10, 1976

Although nobody could have known it then, the guillotine was used for the last time in France on 10 September 1977 in the Baumettes Prison in Marseilles, on a 28-year-old man, Hamida Djandoubi, convicted of murder. Before that, Christian Ranucci, in the same city, on 28 July 1976, and Jérôme Carrein, in Douai on 23 July 1977, went under the blade. They were the last three people to be executed in France, after President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing denied them a pardon, declaring that he wanted to let justice take its course. Christian Ranucci, aged 22, was guillotined despite the fact that doubts – which still remain - were raised about the young man’s guilt. And while Valéry Giscard d’Estaing refused the pardon, Jean Lecanuet, then Minister of Justice, declared two days after the execution: “ Personally, I hope that this act will be exemplary and that those who believed they could commit such odious crimes and escape the most severe of punishments will now measure the risk they are running[1]. »

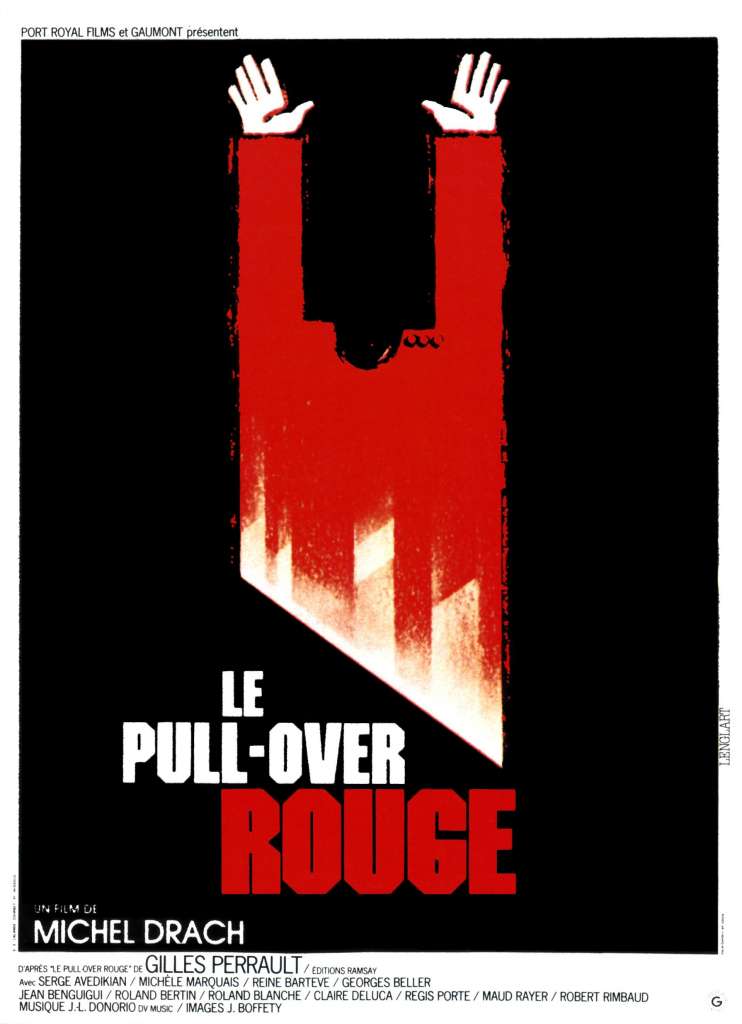

The majority of the public were still in favour of capital punishment. According to a Figaro-Sofres poll of 23 June 1978, 58% of French people supported the death penalty. However, the abolitionist front was growing. This explains why the names of some of the last prisoners sentenced to death have gone down in history, such as Buffet and Bontems or Christian Ranucci. These exceptions, and the intense media profile of their cases, turned them into martyrs for the abolitionist cause. Christian Ranucci was charged with the kidnapping and murder of a young girl, Maria-Dolorès Rambla. In 1978, Gilles Perrault published Le Pull-over Rouge, which raised questions over Ranucci’s innocence, or at least that of a botched investigation and trial, leading to the beheading of a 22-year-old man. Several associations were created, and artists began to campaign for abolition of the death penalty, publicising their position in the media. It should be noted that, to this day, all petitions for a review of the trial - justified in the eyes of the support committee created in 1979 for Ranucci’s rehabilitation, by the grey areas that remain in the case - have been rejected.

Despite all this, on 27 February 1979, a new step towards abolition was taken. The Côte d’Or Court of Assizes sentenced Jean Portais to life imprisonment. This decision was a first, since by refusing to follow the prosecution’s requests, the jurors ensured that there was not a single death row prisoner left in French prisons. It was the only time this situation had arisen prior to the law on abolition. Thus, following difficulties applying the ultimate punishment since the early 1970s, there were moral difficulties pronouncing it at the dawn of the 1980s. This was not systematic. On 11 May 1981, there were eight death row prisoners in French prisons, including Philippe Maurice. He was sentenced for the murder of two policemen on 28 October 1980. It was the first death sentence passed in seventeen years by a Parisian assize court. This was a break with the past. Paris could no longer pride itself on being an advanced city, considering provinces capable of execution to be backward. Paris once again became part of the France of the death penalty.

Nevertheless, from 1977 to 1981, the abolitionist cause went beyond the circle of left-wing members of parliament and intellectuals. In 1977, the Syndicat de la magistrature, a French professional association representing members of the judiciary, came out in favour of abolition, supported by the Fédération autonome des syndicats de police (Autonomous Federation of Police Unions). In October 1977, Amnesty International - promoting universal abolition - was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Boosted by this recognition, the French section of the NGO organised informative debates bringing together abolitionist figures. In January 1978, the Social Commission of the French Episcopate declared itself firmly in favour of abolishing the ultimate punishment. Cardinal Marty stated: “If a man stops behaving like a man, the community must react by not following him.” This was welcome support for abolitionists, as the Catholic Church’s stance gave this struggle strong moral authority.

The abolitionist cause was spreading.

Marie Bardiaux-Vaïente

[1] French National Audiovisual Institute (INA): Interview with Jean Lecanuet, Keeper of the Seals and Minister of Justice, on the death penalty and the execution of Ranucci. Television programme, 8pm news broadcast, journalist Dominique Laury.

- BOOK

Chosen by Fate

Author: McKinley "Malik" Lee, Jr.

Publication Date: 1997

Edited by: Dove Books

A biography of the infamous Death Row Records company is told by a former insider and a respected journalist, providing a balanced look at the history and future of an organization fraught with rumors and violent ends to its artists.

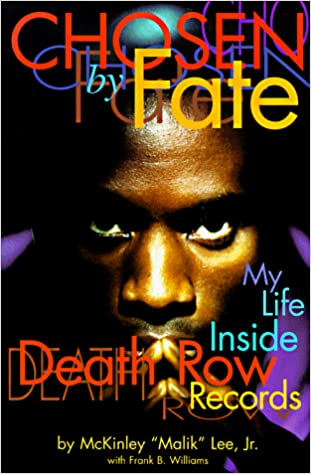

- movie

Le pull-over rouge

Directed by Michel Drach (based on the novel by Gilles Perrault)

Main actors: Serge Avédikian, Michelle Marquais

Production Companies: Gaumont

Native country: France

Genre: Drama

Duration: 120 minutes

Release date: 1979

A film version of author Gilles Perrault's best-selling book about the 1976 trial and execution of Christian Ranucci, the youth who was convicted with extremely inconclusive evidence of murdering an eight-year-old girl in Southern France. The publicity the book and film helped abolish capital punishment in France in 1981.